JACOBSIMEONE.NET

BU Weather Station

By: Jacob Simeone, Published: 2024-06-23

An Introduction

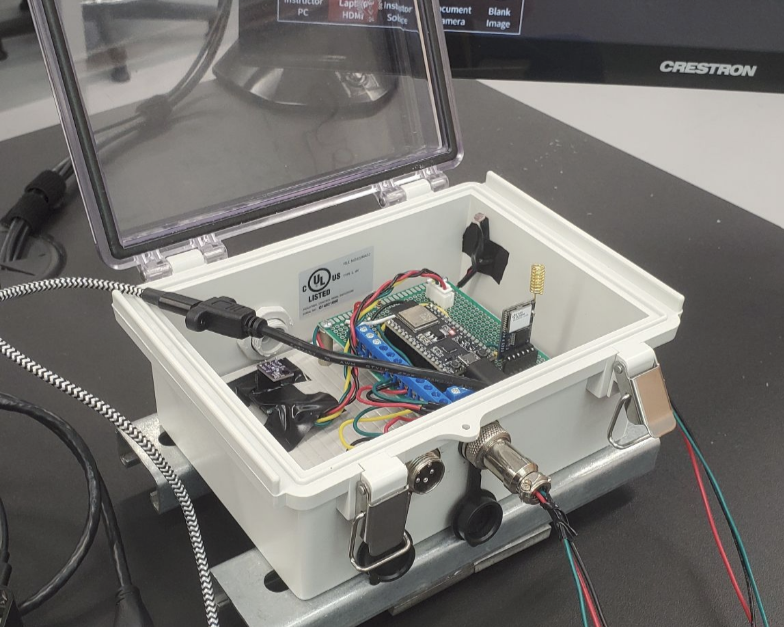

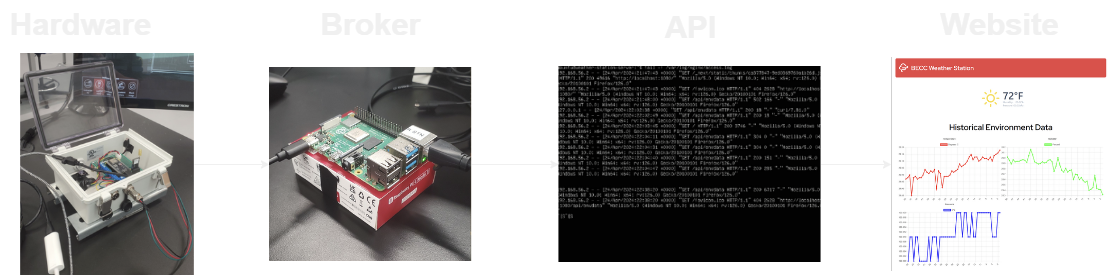

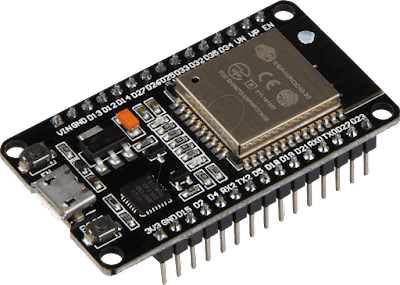

The BU Weather Station is a set of hardware and software that serves the purpose of collecting and reporting environmental data, designed by myself and others at Bradley University. The weather station is for now, publicly hosted at weather.jacobsimeone.net. Pictured above is the actual hardware, made up of a microcontroller, 915 MHz radio, and environmental sensors. Beyond the hardware/firmware, the weather station project also includes two other software components. Firstly, the API, which is responsible for hosting an API that user services can retrieve environmental data from, including websites. Secondly, being the broker, responsible for collecting radio data from the weather station hardware and posting it to the API where it can be requested by users.

Hardware

The hardware on the weather station has three primary jobs: collect environmental data, process that data, and then transmit the data over the radio interface to listening devices. For data collection, the weather station currently employs three different sensors to collect data:

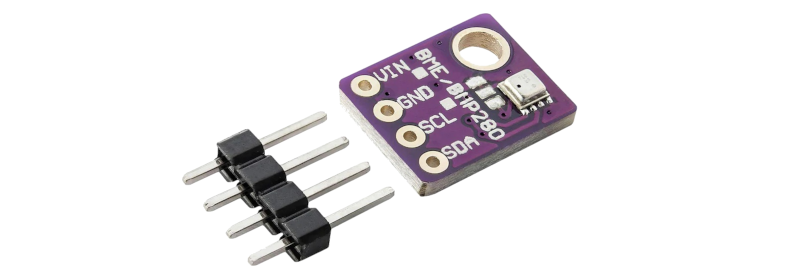

- A BME280, which is used to detect temperature, pressure, and humidity.

- A photoresistor, which is used to determine the light level outside.

- A water level sensor with a custom mount, which is designed to detect if it’s raining.

BME280 Sensor

The BME280 sensor is an environmental sensor common in the hobbyist space, and is typically built into a development board and sold to customers using the Arduino ecosystem. In our case, we purchased one of these development boards carrying the BME280 to work with our ESP32 microcontroller.

The BME280 provides users with temperature, pressure, and humidity data in tolerances good enough for general information over its i2c interface.

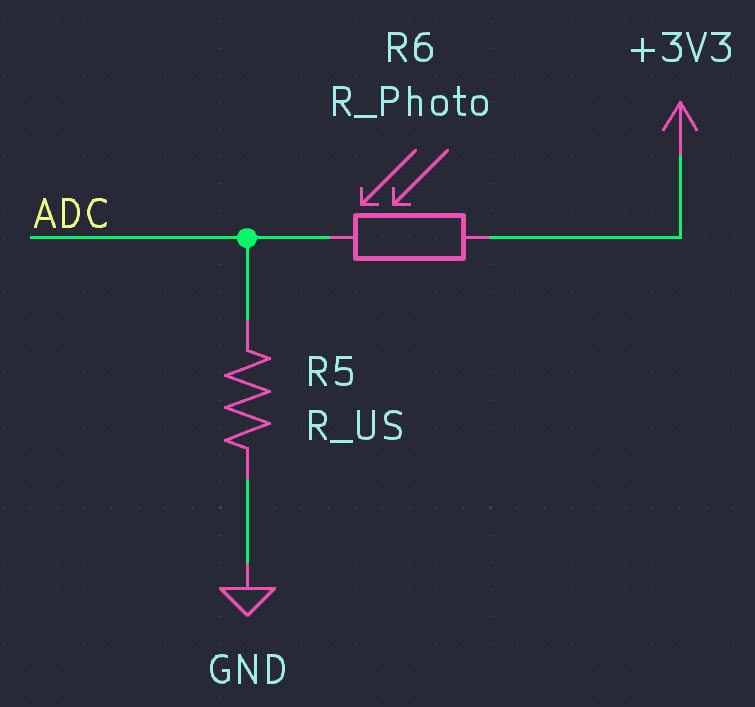

Photoresistor

The Photoresistor is responsible for detecting the light level of the surroundings outside the weather station. Currently, there is no support for translating the photoresistor’s resistance to a physical unit of illumination, just the relative analog value read by the microcontroller.

In order to use the photoresistor, we had to implement a sense circuit which uses a dead-simple voltage divider to create a variable analog output based off the current resistance of the photoresistor. Experimenting with the resistors we had on hand resulted in us choosing a divider like this:

This results in a range of values from the microcontroller’s ADC that can be read and interpreted relative to each other. With testing, we can determine which light levels indicate what kinds of weather conditions (sunny, gloomy, very dark, etc)

Radio

The BU Weather Station needs to transmit its data, otherwise everything that it collects is completely useless. As a group, we decided on wireless transmission, and needed to settle on a technology. Here were the options that came up:

- • WiFi

- • Bluetooth

- • LoRa

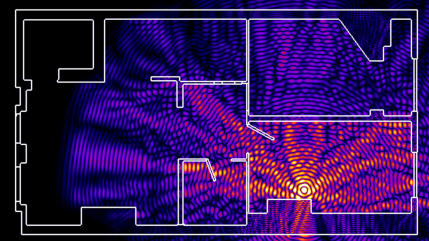

WiFi runs on ~2.4 GHz, which doesn’t have a whole lot of range, in comparison to other technologies. In fact, we estimated that at 2.4 GHz, we would get a range that was roughly 22 meters, given our transmit power and environment. This number was corroborated with testing later.

Bluetooth Runs on the same 2.4 Ghz band, and was thrown out for the same reasons.

LoRa Was promising. It’s a popular, long-range radio protocol that was developed by Semtech, that runs in the 915 MHz ISM band. The radios are cheap and typically compatible with the Arduino ecosystem, making them easy to interface with.

Our group ended up choosing LoRa to communicate with, specifically using the RYLR896 radio, controlled through its serial interface using AT commands. The downside of this radio is it only supports ASCII data, and not custom binary data. Ideally, the radio will be switched later to a radio that supports users sending binary data.

In our implementation, we have a very simple packet that is sent through the radio, which the broker then receives:

T00.00|H00.00|P00.00|R<0 or 1>|L<0,1,2>With T being the temperature, in C, H being the percent humidity, P being the pressure in pascals, R being if it is raining, and L being the light level.

Controller

The brain of the BU Weather Station is an ESP32 microcontroller. This microcontroller is commonly used in the Arduino ecosystem, particularly for projects that must connect through wireless interfaces. We chose this particular microcontroller because it was originally unknown if we were going to use the WiFi or Bluetooth features. Other than that, most microcontrollers would fill the requirements for this project, as long as they had a good i2c and UART interface, as well as an ADC.

Broker

The broker is a piece of software, written in C++ that’s designed to be run on a server that has a matching RYLR896 radio attached over a serial interface, the same as the one running on the BU Weather Station. This software is responsible for receiving the data sent to it by the BU Weather Station, through the radio interface. The Broker then writes this data to an upstream server which hosts the API and a database which holds all of the weather-station data which other services can then query.

API

The API is a very simple service written using Node.js that retrieves data from the redis database, and exposes it through an HTTP API. A user can send a HTTP GET to /api/envdata on the server running the api, and it will return the current environmental data using JSON.

In the future, the API will support retrieving data from specific BU Weather Stations, or more specific data fetching like specific timestamps, or filters users can apply to data.

And returns data in the following format:

{

"weatherData": [

{

"timestamp": "1732851424351-0",

"temp_c": "-0.85",

"humid_prcnt": "54.76",

"pressure_kpa": "100.05",

"is_raining": "0",

"light_level": "DARK"

},

]

}Where:

timestampis milliseconds since epoch, with the sample number for that timestamp appended with a ’-’ character. Like: “[unix-timestamp]-[sample number]”temp_cis the temperature, in degrees celsiushumid_prcntis the relative humidity, as a percent in the range [0-100]pressure_kpain the current pressure, in kpais_rainingis either 0 or 1 to indicate raining.light_levelis either “SUNNY” or “DARK”

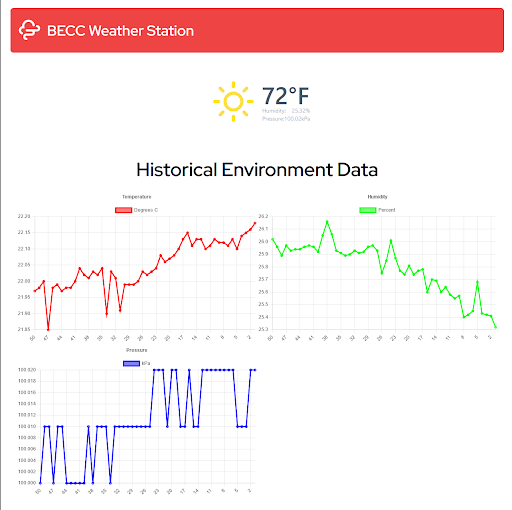

Website

The website is the front-end used to visualize the data collected by the server. This was primarily created as an example for what a user could do with the API running on the server collecting data. Our website is written using the Next.js framework, mainly written in Typescript. In the back-end, the website collects its data from the API running on some server, and displays it to the user:

Future Additions

In the future, I hope to add a couple improvements to the BU Weather Station to both improve the data available, as well as setting up a method to power it in the field, and hopefully more!

Solar & Battery

Currently, the BU Weather Station can only be powered through the debug cable coming out of the station box. In the future, I intend on using a solar panel and internal battery and charger for self-powering in the field, to minimize maintenance.

Lightning Sensor

The weather station presents a unique opportunity to be an on-site early warning system for lightning strikes within a few miles. We plan on using an AS3935 lightning sensor to detect lightning, and potentially create an early-warning system for potentially dangerous storms.

Contributions

Thank you to all of my peers who developed this project with me, at Bradley University.

Last Updated: 2025-01-19